I was really happy to return to Sic (Szék) after a year of not being there. I hadn’t been back for awhile because it’s a heavily Hungarian-speaking village (my Hungarian speaking skills are still sadly low, although my Romanian is getting better), so it requires some planning ahead. I went with translator/brácsás Fenyvesi Attila.

Even though I hadn’t been back in a year, the musicians remembered me. I felt more comfortable with greater knowledge of the music and culture than I had a year ago, and they were more willing to share information.

The part about sheep

The highlight of the trip was visiting Sipos Marci, a brácsás who works full-time as a shepherd, while he was out tending his sheep. He’s out with them pretty much day and night from mid-April till the end of December, coming back to the village just one day per week on the weekends.

We drove to where he was grazing his sheep outside the village: up some steep, rocky roads and past the water tank for the town, up to a ridge with views overlooking the hills and forests on all sides of the village.

As we drove up to where his van is parked, dogs started running and barking next to the car. He has many dogs: as far as I could count, there are 2-3 small dogs which are bred to herd the sheep, and 3-4 large ones which are guard dogs. They are keeping watch for wolves; less frequently, there are bear sightings. Also, since the economy has been bad and with increasing inflation, more people are stealing sheep.

Sipos Marci walked up to us from lower on the slope, where his sheep where grazing. Right now he is tending 780 sheep, and 5 goats. Seemed like a lot to me, but actually 400 more sheep had recently been sold! These sheep are being raised for meat. In the past, he was raising them for milk, and they had to be milked twice a day.

Pointing around to the 360-degree views of rolling hills with close-cropped grass from generations of sheep grazing and patches of forest, Sipos Marci said that he’s taken sheep on all the areas we could see. He’s even grazed them in the forest, where they’ll eat acorns.

From the age of 10, he was helping to herd sheep on school breaks. By the age of 17, he was doing it by himself full-time. He was even raising sheep during his 2-year compulsory military service. During that time, he was taking care of a flock that belonged to the regiment in Bethlen, 50 km from Szék. This was surprising to me, because people have told me it was common to be sent far across the country for military service (and I didn’t know that herding sheep was a military assignment). He said that although he was close to home, the experience was still very difficult: his bosses only spoke to him in Romanian, which he didn’t understand at the time.

However, he remembered some Romanian, and actually spoke to me in Romanian a bit. That was one difference between this visit and last year— the musicians spoke to me a little in Romanian, despite being more comfortable in Hungarian.

He had the small sheep-herding dogs demonstrate how they herd the sheep, and it was a beautiful sight. They quickly ran around the perimeter of the sheep, barking, and the sheep flowed down in an undulating movement.

There is an enclosure for the sheep that they go into at night, a portable fence that needs to be moved every 5 days as to not degrade any one patch of land too much. Marci said that he chooses to wait until it’s completely dark before taking the sheep in, because they’re calmer in the morning that way.

The sheep ended up going into the enclosure on their own while we were talking. Once they were in there, they became totally quiet and still— and that was quite a sight to behold, hundreds of woolly sheep standing in the dark in complete silence.

I asked him if he was lonely there. He said, “yes, it’s lonely… you are far from people. But people are bad, even in the village.”

The part about music

I asked him how he learned to play.

He said that when he was a child, his mother would go to Hungary to sell stuff there. She was able to go only once every two years because border restrictions were strict at the time. When Sipos Marci was 10 or 11 years old, she brought him a furulya (simple wooden flute).

When he was 14, his mom asked him “what do you want (from Hungary)?” He responded, “cigány muzsika” (muzsika is a local name for hegedű, or violin). He associated the violin with Roma (cigány) players because he mostly saw them playing. The next time she went to Hungary, she brought him a violin, and he started to play.

Pali Marci, a Széki prímás around the same age as Sipos Marci, also became interested in the violin at around the same time. Sipos Marci then started playing the brácsa a couple of years later, at 17. At that point, he was out with the sheep most of the time, so Pali Marci had more availability to take gigs as a prímás, so it was more advantageous for Sipos Marci to play the brácsa than the violin.

I asked if there was a particular brácsás he was learning from. He said that he was too young to learn from the band of Icsán (the prímás Adam István “Icsán,” 1909-1980, one of the most revered Széki musicians). He had just come back from the military and within a few years both Icsán and his son, Icsán Pityu, a brácsás, had died.

He said: “Then I was still learning the violin. I was also learning kontra, but there was no one to learn it from. So I would peek” (watch players and pick up things from them).

He mentioned learning some chords from Ilka Gyurika (Széki prímás we watched play with Sipos Marci this year and last year) and his brother Ilka Miki, who was a brácsás.

He also mentioned learning chords from Éri Péter, the brácsás in Muzsikás, one of the most famous bands associated with the táncház movement. He said, “I learned the chords one by one like this as I could see their fingers”.

He then asked Attila “Is your brácsa not here? Let’s bring it down and play a bit. I’ll show you which chord I learned from which musician.”

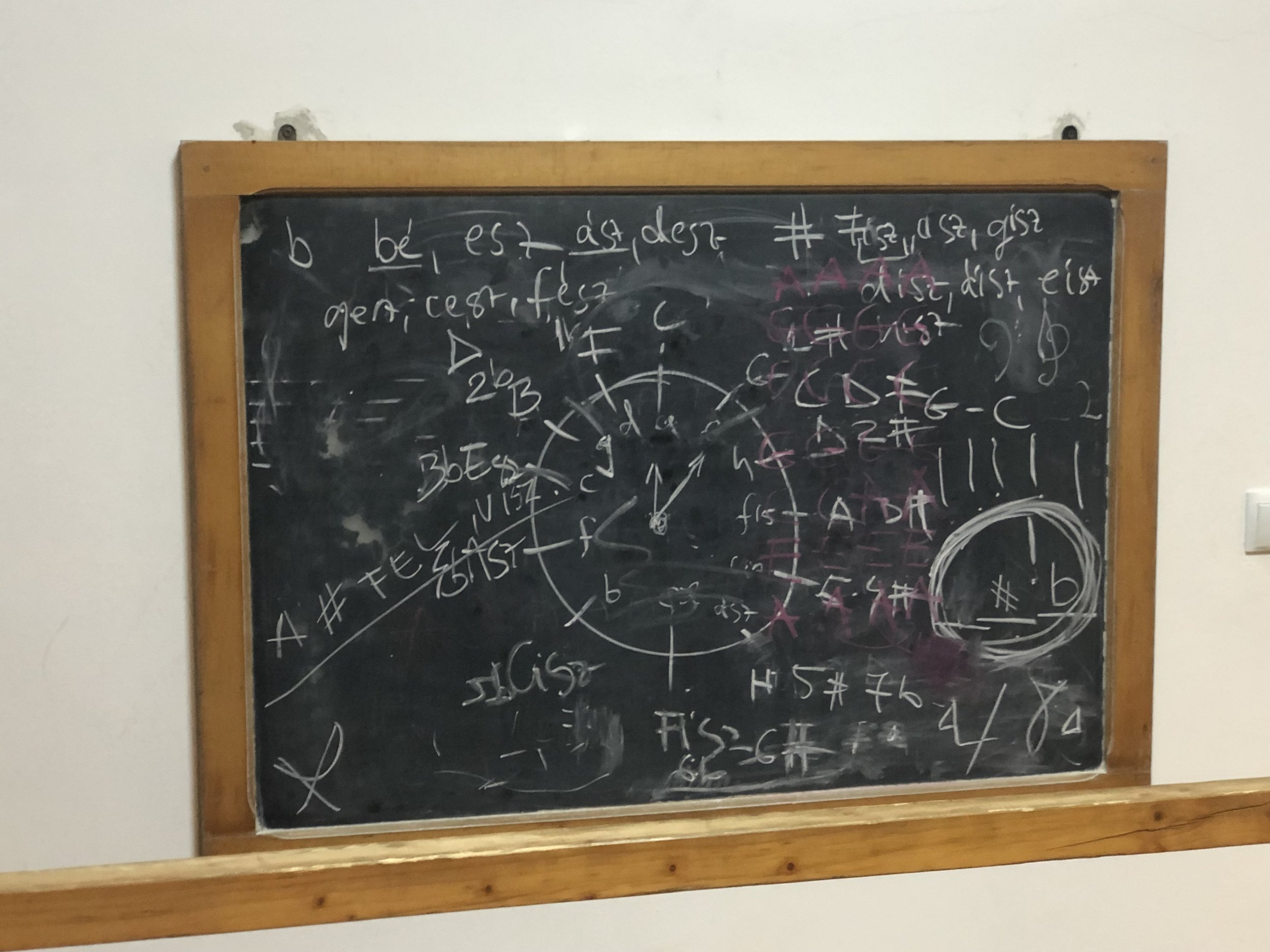

Here’s what he showed us:

He learned C—> D7 from Doór Róbert, the bassist who played with Szalonna.

He learned H—> C°—> E from a brácsás from Bonchida he called Márton bácsi, later adding that that man was a “kicsi törpe ember” (a short gnome guy)

He learned F# (interestingly, he used the Romanian and Hungarian names for this chord: “fa-dièse, or some kind of fisz”) from a bassist in Szamosújvár (Gherla)

He learned G, D, A, E from István Sándor bátya (“bátya” means older brother), the brácsás of Dobos Károly.

Some observations:

— he learned a lot from bassists. When he said “I learned this chord from Doór Róbert”, Attila asked “Doór Róbert played brácsa?”. Sipos Marci said “I don’t know, but he grabbed it and I saw a chord from him”.

— the feedback loop between revival players like Éri Péter and local musicians from Szék is interesting… the more well-known direction of knowledge-sharing is the revival players learning from local Széki musicians, but clearly it went the other way as well.

— he wasn’t demonstrating one chord at a time, but rather a progression of 2 or 3 chords… ie, how he would use them in context.

— his process of chord acquisition (learning chords one by one building on a “vocabulary” he already had, based on what other players might have found lacking in his playing and therefore showed him) reminds me of language acquisition, including my own process of learning Romanian.

Other aspects of the trip

— The day before we arrived in Szék, we visited Ioan Hârleț “Nucu” in Budești. He was in good spirits and played well. He played some melodies which I hadn’t heard him play in any of my previous visits there.

— We attended folk music/dance events in Gherla (Szamosújvár) and Vișea (Visa), which are both in the vicinity of Szék. One highlight of the event in Visa was seeing old couples dance, backed up by the Palatkai band.

— We also had the chance to visit with Sallai Pista bácsi, the old singer/dancer, and buy some pálinka from him.

— People from Szék are known for being hard-working, and this seems particularly true now, with the current tough economic outlook. Gyurika and Pali Marci both work construction jobs, and their wives are doing domestic work in Cluj 5 or 6 days a week, only coming home for a day or 2 on the weekends.

— Our trip wrapped up nicely with listening to/jamming with Gyurika and Sipos Marci, with some singing and dancing from Sallai Pista bácsi.